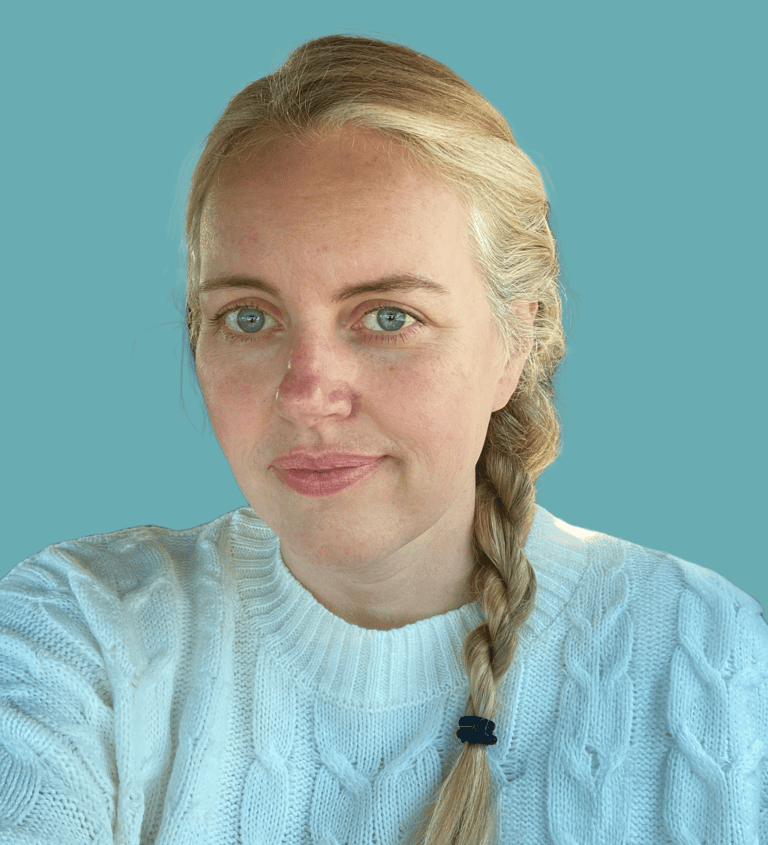

Meet Laura Hamann

STUDENT RESEARCHER

I’m currently at the University of Louisville, where I study biology with an eye on the clinical applications of extremophiles. I coauthored a forthcoming paper on IUD biofilms (ask me about the stuff we found—it’ll ruin brunch), helping make sense of the microbial data and tying it to the bigger clinical picture. Now I’m knee-deep in cave isolates, antibiotic resistance screens, and wild hypotheses that just might work.

I didn’t grow up in a system built for women like me. Honestly, I wasn’t one either. I had to become someone new—someone who took the trauma, the doubt, and the deep sense of not belonging, and lit it all on fire. I went from “I can’t” to “I will,” and then, “I’ll show you how too.” What came out of that fire was confidence, resilience, and a drive not just to reach my goals, but to motivate others who’ve felt inadequate or out of place to realize they’re more than enough.

Before I was ever officially part of formal science, I was already researching—digging deep into topics that mattered to me. Coming back to school in my 40s, I finally found my people: those lit up by the wonder and mystery of science, especially medical science. I believe some of the most urgent medical solutions, like how to fight antibiotic resistance, are already within reach. We just have to look in unexpected places.

I spent many years raising a family with my husband of over 25 years, while fiercely advocating for our children—starting when our oldest was diagnosed with autism at age three. Navigating complex systems, pushing for what they needed to thrive, and learning to speak up in rooms that weren’t built for us all sparked a fire in me that still burns. That same fire—fueled by growth, grit, and a belief in what’s possible—eventually turned inward, driving me to reclaim my own path. I’ve been a PTA VP, a theater board member, and the president of a local women’s organization. I’ve always been driven by a belief in the power of voices, especially those that often go unheard. Now I bring all of that lived experience into the lab. I don’t separate life from learning, I blend them like reagents and make meaning from the reaction.

The kind of science I believe in doesn’t stay in its lane. The problems we face, like antibiotic resistance and environmental disease, won’t be solved by a single discipline. I’m passionate about cross-collaborative research that brings together geologists, microbiologists, clinicians, and creative thinkers from every background. I believe in breaking down academic silos to build something better—where discovery isn’t just the goal, but a tool for real-world change.

The CHAOS Lab is the perfect vessel for that kind of work. It’s a medical-geoscience lab led by a testicular immunologist who once worked in special ops. How could it not be the ideal place for curiosity-fueled, discipline-busting research? Long before I knew I belonged in science, Dr. Rachel Washburn saw potential in me as a scientist and opened the door. Her belief set me on the path I’m now charging down. My sights are set on a PhD in clinical microbiology.

When I’m not working on school or advancing science, you’ll probably find me on the pickleball court, kayaking down a quiet creek, or casting a line—all with family and friends in tow. I’m not a runner by nature, but peer pressure works. I recently trained for and completed a 10K (and passed calculus with an A, which may have been the harder of the two).

I also love tinkering at my local library’s makerspace, especially with the laser cutter. There’s something deeply satisfying about turning ideas into tangible things. And yes, watching the machine slice through materials with surgical precision might be my version of a mindfulness exercise. It’s also where I 3D-printed a model of my favorite virus, the T4 bacteriophage. With its spider-like landing gear and spring-loaded injection system, it looks like a tiny alien war machine—and it kind of is.

Eventually, I hope to work with tools like laser capture microdissection to isolate microbial structures, or geoscience technologies like laser ablation to help uncover how environmental systems can inform clinical solutions. I’d also love to work directly with bacteriophages like the T4, applying their molecular precision to problems like antimicrobial resistance. These viral tools aren’t just wicked to look at—they’re being explored for serious applications in medicine and biotechnology.

Whether in the lab or the field, the precision of these technologies speaks to something in me: a fascination with sharp tools, fine detail, and the pursuit of meaning in the smallest layers of the world.